The continuing impact of the West Coast port disruptions

March 9, 2015 by Marty Lariviere

The West Port labor strife is now over but issues remain. There are still dozens of ships waiting for their turn at Southern California ports and there are numerous bottlenecks in getting containers off ships and to their destinations. The Wall Street Journal has had a couple of recent articles dealing with how these logistical disruptions have affected supply chains as well as how the ports might possibly run better.

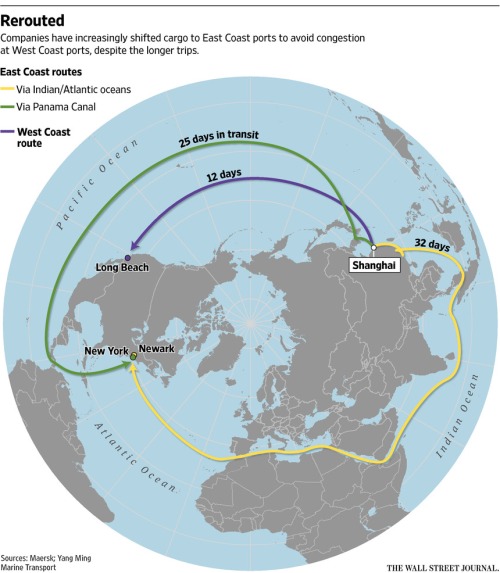

First up is how the ports customers are reacting (Ports Gridlock Reshapes the Supply Chain, Mar 5). The West Coast doesn’t have a monopoly on US ports, of course; they are just the most convenient to Asia. However, as the graphic above demonstrates, shipping to the East or Gulf Coasts are an options if you are willing to wait a bit longer to get your goods. Currently, the West Coast handles about half of US cargo shipments but, according to an executive of the Port of Los Angeles, a third of their volume is “purely discretionary” in the sense that it could go to another port.

The biggest shippers, including Wal-Mart Stores Inc., Home Depot Inc. and Target Corp. , have employed for years what is known in the industry as a four-corner strategy, in which networks are expanded to include warehouses at northern and southern ports on both coasts and the Gulf of Mexico. Now even smaller companies are diversifying.A survey of 138 shippers last week by the Journal of Commerce showed that 65% said they planned to ship less cargo through the U.S. West Coast through 2016, with a similar percentage planning to permanently reroute some cargo.

Scale obviously matters here. There are going to be a lot of fixed costs involved in processing containers and getting stuff out of ships and on to stores or factories. If you import stuff at the rate of Wal-Mart or Home Depot, you don’t lose much by doing this on both coasts. For smaller firms, duplicating operations is more painful but becomes more worthwhile as West Coast service suffers.

What the article doesn’t say is how much of that rerouted cargo is coming by boat to a different port versus being flown in. Air freight is costlier but offers greater flexibility and speed. The extra cost then brings improved performance as opposed to a sluggish supply chain.

The second article is about the flow of containers within the port — or more accurately the process of getting a container onto a truck and on its way (Ports Get Creative as Cargo Piles Up, Mar 1). The conventional process has a driver showing up to get a specific container. If that container is not conveniently on top of a near-by pile, the driver waits for the right container to be dug out. But some terminal are experimenting with a new approach.

So some terminals have been trying a novel idea: When a truck driver shows up, put the first container off the top of the stack on the truck and send it on its way. No more moving other containers around to dig out specific cargo—just get it all off the dock as fast as possible.The concept isn’t entirely new. Many megaretailers use what is known as free-flow or peel-off operations at the ports. If there are enough containers destined for the same cargo owner, all arriving on the same ship, longshore crane operators can stack them together and load them on to the retailer’s trucks as they arrive.Now Mr. Molinaro and his team are testing a way to make “free flow” possible for smaller retailers too, using Cargomatic’s new smartphone-based Uber-style app. Drivers show up to the West Basin Container Terminal—again, no appointment necessary—and are given the first container off the top of the “Cargomatic pile,” or goods destined for any customer signed up for the program. The driver logs the pickup in the app, which provides instructions on where to take the container and pays the driver automatically. (Currently, deliveries are limited to within 150 miles of the port.)

You can see a video with the system in operation here.

This is a nice example of resource pooling. By having a set of containers that can be taken by the first available truck, containers and trucks can get out of the port terminal more quickly. The article reports that trucks are in and out of the port in 35 minutes — half the time of the standard process. That’s fairly significant. If driver’s work ten-hour shifts and deliver four loads per shift under the current system, this new approach would allow them to squeeze in another load per day — that matters when you get paid per load.

Two points seem worth making. First, technology makes this easier. Mentioning an “Uber-style app” is a little deceptive. It is not that drivers are being called for specific loads. The key thing is that drivers are able to learn automatically where they should be taking their new load. That is, it is the automatic mapping that matters. Second, scale is again going to matter. Wal-Mart can fill enough containers on its own that the port will treat them special. Smaller importers don’t have that luxury. Grouping containers across firms, however, leads to the necessary scale.

No comments:

Post a Comment