Why Your Next Package Will Be Delivered By An Uber

Geographic saturation is the key to network effects and profitability in the ridesharing business.

The more drivers Uber or Lyft have in a given region, the faster the pick-up times, the better the customer experience and the more rider demand — which in turn allows drivers to earn more money and attracts more drivers to the network.

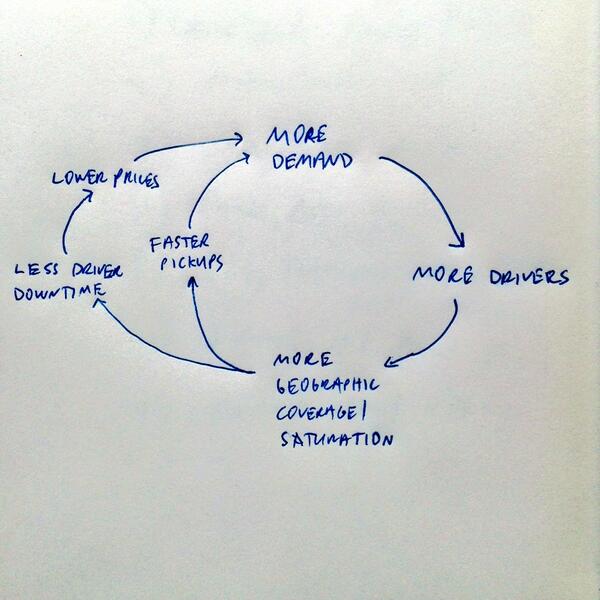

David Sacks best illustrated Uber’s positive feedback cycle last year:

If Sacks is right, that the ridesharing provider with the most geographic saturation ends up with the lowest costs and best rider experience, then the strategy is clear: Raise as much money as possible to subsidize both supply and demand in what, to some observers, appears to be a winner-take-all market.

But do Uber’s network effects really scale infinitely, or will they reach a point of decreasing marginal returns? Could Lyft achieve parity in pickup wait times and driver downtime with only a fraction of Uber’s scale?

Let’s imagine that Uber achieves a geographic saturation advantage of 10 or even 100 times more drivers in a given area than Lyft (realistically this is unlikely, given the ease with which drivers can work for both services simultaneously). But even if Lyft did concede such an enormous advantage, one could envision the ridesharing market expanding to the point where they get a driver to pick you up within three minutes every time.

What’s the difference between getting picked up in one minute and three minutes? Not much.

If Lyft can hit that target, they will have negated Uber’s route-density advantage, and with it, a major premise of the financing arms race. At that point, we would expect Lyft to steadily gain market share as the two companies’ core value propositions become even less differentiated.

What do these decreasing marginal returns to route density mean for Uber’s strategy? Is there some other valuable market where it’s unprecedented route density might be valuable?

Overwhelming route density has made it nearly impossible for new entrants to gain a foothold in the parcel business.

Yes. The same economies of scale apply in the last-mile logistics business, where FedEx, UPS and USPS have managed to achieve supreme geographic saturation. Because these companies have drivers on almost every block in America on a daily basis, their marginal cost to deliver one more parcel is as low as $1.50. And if they have two parcels to deliver to the same house, the cost to deliver the second one falls to almost zero.

This overwhelming route density has made it nearly impossible for new entrants to gain a foothold in the parcel business. Even DHL, which has a top-three worldwide parcel delivery network, failed in its bid to enter the domestic market, withdrawing in late 2008.

But Uber has a key advantage over even these massive incumbents: While the big parcel players put a driver on every block every day, in metropolitan regions Uber has drivers on every block every minute.

While both FedEx and UPS do offer scheduled pickups, only Uber (and perhaps someday Lyft) has the density needed to offer instant pickups and on-demand deliveries. This is a game-changer, as it enables a whole new generation of real-time e-commerce experiences.

Already customers of Uber Pool have shown a willingness to ride with a stranger in exchange for a discount. Surely they would make the same trade to allow the driver to stop to let a customer put a package in the car’s trunk. And if the driver stopped to deliver a package, it also wouldn’t feel much different from the current Uber Pool experience.

Likely the same driver wouldn’t need to pick up and then deliver the parcel as with courier services like Postmates. Rather the driver would simply accumulate packages in the trunk throughout the day, then drop them all off at a consolidation center at the end of their shift.

Uber has already begun their shift toward becoming a real-time logistics network, rather than a mere ridesharing service. They’ve launched Uber Cargo in Hong Kong and Uber Rush in New York City. For the time being, those services use separate networks of cargo vans and bike messengers, respectively. But it’s only a matter of time before we see Uber roll out parcel solutions that leverage their dense network of ridesharing drivers.

The first order analysis of why this matters is obvious: Logistics is 12 percent of global GDP, so the parcel business represents a huge new revenue stream for Uber. The second order analysis is perhaps more interesting: Parcels and people can cross subsidize each other, so by co-existing, the two services are cheaper than either could be alone.

Parcel delivery services will become a powerful lever for Uber in its rivalry with Lyft. Suddenly Uber changing its tagline from “Everyone’s private driver” to “Where lifestyle meets logistics” makes a lot more sense. Pulling off that change all the way back in 2013 shows that Uber has one of the most forward-looking management teams in business.

No comments:

Post a Comment