Intermodal Boom Will Revolutionize Supply Chain Logistics and Industrial Real Estate Strategy

A looming capacity shortage in the trucking industry — coupled with rail’s high efficiency — is causing logistics suppliers and transportation providers to turn their focus to intermodal solutions.

BNSF at Logistics Park KC

BNSF at Logistics Park KC

Similar to its starring role in the 19th century westward expansion, rail — the “Iron Horse” — is picking up steam. Though trucks remain today’s primary shipping method for domestic freight distribution, rail is fast emerging as a top criterion in both logistics strategy and industrial real estate development.

According to new JLL research, a looming capacity shortage in the trucking industry — coupled with rail’s high efficiency — is causing logistics suppliers and transportation providers to turn their focus to intermodal solutions. As a result, 30 inland port facilities have either opened or been formally announced since 2000 — including 19 since 2008 alone.

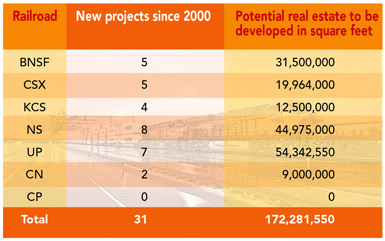

These new intermodal facilities could spark the development of another estimated 172.3 million square feet of related facility and industrial space. When combined with business park infrastructure costs, they could represent investment potential above $10 billion. While these are just estimates, the indicators point to a looming reality for multiple regions.

All Signs Point to Intermodal

The trend toward intermodal facilities/inland ports is relatively new — and has taken off fast. In 1980, the volume of U.S. cargo carried by rail as part of an intermodal distribution system was just 3.1 million containers and trailers. By 2013 that volume had quadrupled, reaching 12.8 million units. Moreover, the American Association of Railroads reports that by March of this year, intermodal traf?c had risen over 9.9 percent from March 2013, representing the 52nd consecutive year-over-year monthly increase. It stands to reason that marrying the best of both rail and truck capacity could help drive costs out of the supply chain, while empowering more efficient goods delivery.

Taking a step back from the numbers, it stands to reason that marrying the best of both rail and truck capacity could help drive costs out of the supply chain, while empowering more efficient goods delivery. So why are we seeing an increased push to intermodal facilities now? There are a few factors in this fast-emerging industrial development strategy, including:

The desire to develop highly functional inland ports is well beyond the conceptual phase. Coinciding with the rise in intermodal transport, there has been a marked increase in industrial facility development near rail yards. In JLL’s recent sampling of 250,000-square-feet-plus warehouse/distribution facilities located within a five-mile radius of U.S. rail yards, roughly half of the 574 buildings surveyed had been built after the year 2000.

For inspiration, consider the example of Alliance Texas, developed by a partnership between a railroad and real estate developer that was the first fully integrated modern inland port/intermodal facility in the country. Sprawling across 17,000 acres, this inland port features both a Burlington Northern Santa Fe (BNSF) intermodal facility and an airport.

Markets with intermodal rail facilities currently boast the highest rent growth — a trend we expect to continue as the Iron Horse regains its prominence in modern industrial expansion.Public agencies are also serving as important partners. Spurred by the Transportation Investment Generating Economic Recovery (TIGER) portion of the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009, the Department of Transportation’s competitive grants have allotted roughly $4.2 billion to capital investments in surface transportation infrastructure. Inland port grant recipients have included the Northeast and Midwest U.S. National Gateway Project, which connects Northwest Ohio to Chambersburg, Pennsylvania; the Crescent Corridor Intermodal Freight Program rail projects in Memphis and Birmingham; and several intermodal facilities in the Los Angeles/Long Beach area.

Railroad executives are involved too, beefing up infrastructure and modernizing facilities in large metro areas like Atlanta and Chicago, as well as identifying new areas for facility construction and line expansion. In a February 2014 press release, the CSX Railroad estimated that nine million truckloads in the eastern U.S. could be candidates for intermodal rail conversion; it is, therefore, investing $2.3 billion in intermodal facilities in Florida and Canada.

Meanwhile the Norfolk Southern (NS) plans to invest $2.5 billion in new facilities and infrastructure for its Crescent Corridor line, which spans 11 states from the Southeast to the Northeast, based on the notion that demand will enable the line to remove an estimated 1.3 million long-haul trucks annually.

Mapping Market Demand for Intermodal Development

While new intermodal developments are cropping up across the country, three major markets are seeing the most near-real construction activity: Dallas/Fort Worth, Central Pennsylvania, and Northern New Jersey together account for 51 percent of rail-near-big-box development activity, or 10.1 million square feet of the 19.8 million square feet currently under way.

These three otherwise diverse markets share some important traits: land availability, a sizable population, and, perhaps most importantly, inland ports with rail connectivity to other major cities. For example, Dallas/Fort Worth, which holds first place in near-real construction across all markets, offers rail connectivity to both Chicago (the nation’s busiest inland port), and Southern California (the busiest seaports, through which 40 percent of imports enter the U.S.).

Following are some other market highlights:

Illinois: Since opening the highly successful BNSF Logistics Park-Chicago in 2002, the Prairie State has recently added to its intermodal roster the RidgePort Logistics Center — a 1,500-acre development with construction potential for almost 15 million square feet of space — and the Union Paci?c-Joliet Intermodal Center, which offers construction potential for an additional 20 million square feet.

Kansas: Open since late 2013, the BNSF Intermodal and Logistics Park KC sits on the transcontinental line between Chicago and the ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach. Its current annual capacity of 500,000 container lifts is expected to triple to 1.5 million upon build-out, and to attract 100 million square feet of new industrial development within a 350-mile radius.

North Carolina: More than 15 million square feet could be developed in conjunction with the unique Charlotte Regional Intermodal Facility, which opened in December 2013 thanks to a partnership between Norfolk Southern and municipal authorities, including the city of Charlotte and Charlotte Airport.

From coast to coast, inland ports are poised to revolutionize both supply chain logistics and industrial real estate strategy. Maximizing the efficacy and value of distribution by developing modern intermodal facility space can improve connectivity between the nation’s markets, as well as add significant value to the entire network of supporting partners, from developers and corporate occupiers to distribution, logistics, and transport professionals alike. Case in point: Markets with intermodal rail facilities currently boast the highest rent growth — a trend we expect to continue as the Iron Horse regains its prominence in modern industrial expansion.

According to new JLL research, a looming capacity shortage in the trucking industry — coupled with rail’s high efficiency — is causing logistics suppliers and transportation providers to turn their focus to intermodal solutions. As a result, 30 inland port facilities have either opened or been formally announced since 2000 — including 19 since 2008 alone.

These new intermodal facilities could spark the development of another estimated 172.3 million square feet of related facility and industrial space. When combined with business park infrastructure costs, they could represent investment potential above $10 billion. While these are just estimates, the indicators point to a looming reality for multiple regions.

All Signs Point to Intermodal

The trend toward intermodal facilities/inland ports is relatively new — and has taken off fast. In 1980, the volume of U.S. cargo carried by rail as part of an intermodal distribution system was just 3.1 million containers and trailers. By 2013 that volume had quadrupled, reaching 12.8 million units. Moreover, the American Association of Railroads reports that by March of this year, intermodal traf?c had risen over 9.9 percent from March 2013, representing the 52nd consecutive year-over-year monthly increase. It stands to reason that marrying the best of both rail and truck capacity could help drive costs out of the supply chain, while empowering more efficient goods delivery.

Taking a step back from the numbers, it stands to reason that marrying the best of both rail and truck capacity could help drive costs out of the supply chain, while empowering more efficient goods delivery. So why are we seeing an increased push to intermodal facilities now? There are a few factors in this fast-emerging industrial development strategy, including:

- Trucking capacity shortage: A truck-only approach is no longer sustainable. “The mother of all capacity shortages” is coming, predicts the National Transportation Institute Founder and President Gordon Klemp. This widely expected shortage stems from several factors, from new restrictions on the number of hours drivers can be on the road and rising insurance costs, to the fact that fewer members of the new working generation are pursuing trucking careers compared with their close-to-retirement counterparts.

- Increasing demand for efficiency: High-speed delivery for the lowest cost possible is becoming the norm rather than the exception, and rail transport is typically four times more fuel-efficient than truck transport, thus playing a significant part in its growing appeal. Trains are also more efficient than trucks in terms of the amount of cargo they can carry, considering that shipping containers can be double-stacked on trains, driving productivity across the board. This efficiency extends to environmental impact, too, with rail transportation considered 60 percent more environmentally friendly than truck transportation.

- The need to reduce risk: A well-documented increase in natural disasters around the world can have many consequences, including seriously impairing distribution logistics by blocking or destroying roads, stymying drivers, or simply creating unforeseen traffic snarls. Together with truck driver shortages, these risks are inspiring many supply chain professionals to minimize risk by investing in developing more than one way to transport goods.

The desire to develop highly functional inland ports is well beyond the conceptual phase. Coinciding with the rise in intermodal transport, there has been a marked increase in industrial facility development near rail yards. In JLL’s recent sampling of 250,000-square-feet-plus warehouse/distribution facilities located within a five-mile radius of U.S. rail yards, roughly half of the 574 buildings surveyed had been built after the year 2000.

In JLL’s recent sampling of 250,000-square-feet-plus warehouse/distribution facilities located within a five-mile radius of U.S. rail yards, roughly half of the 574 buildings surveyed had been built after the year 2000

More than ever, we are seeing growing collaboration between supply chain professionals, transportation providers, third-party logistics companies, corporate shippers, and real estate developers and owners, who — by working together — can identify the best land opportunities capable of aggregating rail and truck traffic.For inspiration, consider the example of Alliance Texas, developed by a partnership between a railroad and real estate developer that was the first fully integrated modern inland port/intermodal facility in the country. Sprawling across 17,000 acres, this inland port features both a Burlington Northern Santa Fe (BNSF) intermodal facility and an airport.

Markets with intermodal rail facilities currently boast the highest rent growth — a trend we expect to continue as the Iron Horse regains its prominence in modern industrial expansion.Public agencies are also serving as important partners. Spurred by the Transportation Investment Generating Economic Recovery (TIGER) portion of the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009, the Department of Transportation’s competitive grants have allotted roughly $4.2 billion to capital investments in surface transportation infrastructure. Inland port grant recipients have included the Northeast and Midwest U.S. National Gateway Project, which connects Northwest Ohio to Chambersburg, Pennsylvania; the Crescent Corridor Intermodal Freight Program rail projects in Memphis and Birmingham; and several intermodal facilities in the Los Angeles/Long Beach area.

Railroad executives are involved too, beefing up infrastructure and modernizing facilities in large metro areas like Atlanta and Chicago, as well as identifying new areas for facility construction and line expansion. In a February 2014 press release, the CSX Railroad estimated that nine million truckloads in the eastern U.S. could be candidates for intermodal rail conversion; it is, therefore, investing $2.3 billion in intermodal facilities in Florida and Canada.

Meanwhile the Norfolk Southern (NS) plans to invest $2.5 billion in new facilities and infrastructure for its Crescent Corridor line, which spans 11 states from the Southeast to the Northeast, based on the notion that demand will enable the line to remove an estimated 1.3 million long-haul trucks annually.

Mapping Market Demand for Intermodal Development

While new intermodal developments are cropping up across the country, three major markets are seeing the most near-real construction activity: Dallas/Fort Worth, Central Pennsylvania, and Northern New Jersey together account for 51 percent of rail-near-big-box development activity, or 10.1 million square feet of the 19.8 million square feet currently under way.

These three otherwise diverse markets share some important traits: land availability, a sizable population, and, perhaps most importantly, inland ports with rail connectivity to other major cities. For example, Dallas/Fort Worth, which holds first place in near-real construction across all markets, offers rail connectivity to both Chicago (the nation’s busiest inland port), and Southern California (the busiest seaports, through which 40 percent of imports enter the U.S.).

Following are some other market highlights:

Illinois: Since opening the highly successful BNSF Logistics Park-Chicago in 2002, the Prairie State has recently added to its intermodal roster the RidgePort Logistics Center — a 1,500-acre development with construction potential for almost 15 million square feet of space — and the Union Paci?c-Joliet Intermodal Center, which offers construction potential for an additional 20 million square feet.

Kansas: Open since late 2013, the BNSF Intermodal and Logistics Park KC sits on the transcontinental line between Chicago and the ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach. Its current annual capacity of 500,000 container lifts is expected to triple to 1.5 million upon build-out, and to attract 100 million square feet of new industrial development within a 350-mile radius.

North Carolina: More than 15 million square feet could be developed in conjunction with the unique Charlotte Regional Intermodal Facility, which opened in December 2013 thanks to a partnership between Norfolk Southern and municipal authorities, including the city of Charlotte and Charlotte Airport.

From coast to coast, inland ports are poised to revolutionize both supply chain logistics and industrial real estate strategy. Maximizing the efficacy and value of distribution by developing modern intermodal facility space can improve connectivity between the nation’s markets, as well as add significant value to the entire network of supporting partners, from developers and corporate occupiers to distribution, logistics, and transport professionals alike. Case in point: Markets with intermodal rail facilities currently boast the highest rent growth — a trend we expect to continue as the Iron Horse regains its prominence in modern industrial expansion.

No comments:

Post a Comment