Study: to excel at omnichannel distribution, you need the right stuff

Everyone wants to be the master of the omnichannel universe. But our exclusive study shows that most companies have been reluctant to make the necessary investment in distribution technology.

As retail goes omnichannel, many distribution operations are undergoing a seismic shift. That's particularly true of conventional retailers, which once only had to worry about keeping their store shelves stocked. These days, that's not enough. When it comes to the shopping experience, today's consumers expect to move effortlessly between the physical and digital worlds—they want the option to buy online and pick up at the store, or buy at a store and have the order delivered from a warehouse/DC—or even another store. That puts enormous pressure on the retailer's order fulfillment and distribution operations to integrate their store and digital selling channels to work seamlessly together.

To get a better understanding of how this has affected distribution operations, DCV and ARC Advisory Group teamed up last year to conduct the inaugural omnichannel distribution study. Among other findings, the research indicated that retailers' service ambitions often outpaced their capabilities. That is, although they offered customers a wide array of omnichannel services, they didn't always have the proper groundwork in place—particularly at the store level.

To see what progress has been made in the past year, DC Velocity and its sister publication, CSCMP's Supply Chain Quarterly, teamed up with ARC Advisory Group to conduct a follow-up study—one that would take a deeper dive into the details of DC operations that support omnichannel initiatives. This year's survey sought to answer a number of key questions: How far have retailers progressed down the omnichannel road? How are they responding to the new demands of an "anything, anytime, anywhere" retail environment? And what tools and technologies are they using to manage their operations?

THE WHYS AND HOWS

Given all the headaches involved, it seems fair to ask why companies get involved in omnichannel in the first place. As the study made clear, most consider omnichannel a business imperative. When asked to name their top reason for engaging in omnichannel commerce, 83 percent of respondents said their objective was to increase sales—up slightly from last year's 78 percent. In both years' studies, the second and third most frequent responses were to boost market share and to increase customer loyalty.

Given all the headaches involved, it seems fair to ask why companies get involved in omnichannel in the first place. As the study made clear, most consider omnichannel a business imperative. When asked to name their top reason for engaging in omnichannel commerce, 83 percent of respondents said their objective was to increase sales—up slightly from last year's 78 percent. In both years' studies, the second and third most frequent responses were to boost market share and to increase customer loyalty.

As for what sales channels the respondents are using, 38 percent are engaged in "direct sales" to the customer or consumer, meaning they sell the merchandise themselves either in a brick-and-mortar store or through a Web store or catalog operation. Another 10 percent engage in "indirect sales," working with suppliers or manufacturers that provide and ship the merchandise on the retailer's behalf. The remaining 52 percent are using a combination of direct sales and indirect sales.

Not surprisingly, the study indicated that the Internet has become a primary sales channel for consumer goods. Eighty-two percent of survey participants were selling products online, while only 70 percent were engaged in traditional brick-and-mortar retailing. Another 52 percent said they did either call center or catalog selling. (Respondents were allowed to select more than one option.)

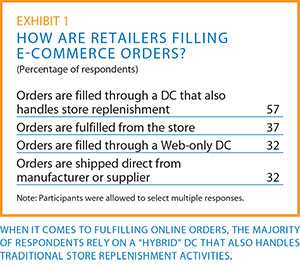

As to how they're handling fulfillment of e-commerce orders, 57 percent are using stock from distribution centers that support both e-commerce and store replenishment. Another 37 percent are taking merchandise from store shelves, while 32 percent use a Web-only DC. (See Exhibit 1.)

When it comes to who operates those e-commerce distribution centers, 17 percent outsource the operations to a third-party logistics (3PL) company. Still, the majority—62 percent—run their own facilities for e-commerce pick-pack-and-ship, while another 21 percent use a combination of company-owned and outsourced facilities.

Retailers are embracing the "common pool of inventory" concept, meaning they use any available inventory, no matter the location, to fill both online and store orders. Exactly half the respondents—50 percent—share direct sales inventory across all channels. Another 32 percent said they had plans to move in that direction.

As for how retail outlets fit into the e-commerce fulfillment picture, the study indicated that stores play a variety of roles. Eighty-six percent of respondents that use retail outlets to fill online orders said they picked and shipped online orders from stores. Another 68 percent picked orders and held them at the store for customer pickup, while 45 percent had their DCs ship merchandise to the store for customer pickup. (Respondents were allowed to select more than one option.)

For online orders picked from retail outlet stock, 90 percent of respondents said they selected items from the front of the store and 71 percent pulled items from the backroom. As for how store management is communicating information on what items to pick, the majority—71 percent—are using a paper-based method to convey instructions to order selectors. Thirty-eight percent are using some type of radio-frequency communication, although some of those respondents are doing so in conjunction with a paper-based approach.

The use of paper-based picking in stores stands in sharp contrast to the automated processes found in today's distribution centers. When respondents were asked what order fulfillment technologies they employed in their DCs, the majority—64 percent—said they used a warehouse management system (WMS) in combination with radio-frequency technology, an approach that allows order selectors to receive instructions in real time as they move about the facility. Still, a third of DCs perform order selection the old-fashioned way, using a paper-based process in conjunction with their WMS. Another 16 percent have deployed a voice-recognition system, while 6 percent were using goods-to-person automation and 6 percent a pick-to-light system.

SEPARATE BUT UNEQUAL?

With well over half the respondents filling both e-commerce and store replenishment orders from a single DC, the question arises as to how they handle these "hybrid" operations. The survey results indicated that most separate the two activities. Fifty-seven percent of respondents said they segregated their e-fulfillment operations from their traditional store fulfillment activities. Eighty-five percent of respondents segregating e-fulfillment reported that they had a separate, distinct area for e-commerce within the warehouse. Along with the physical separation, many respondents said they maintained distinct inventory for e-commerce as well as separate labor forces.

With well over half the respondents filling both e-commerce and store replenishment orders from a single DC, the question arises as to how they handle these "hybrid" operations. The survey results indicated that most separate the two activities. Fifty-seven percent of respondents said they segregated their e-fulfillment operations from their traditional store fulfillment activities. Eighty-five percent of respondents segregating e-fulfillment reported that they had a separate, distinct area for e-commerce within the warehouse. Along with the physical separation, many respondents said they maintained distinct inventory for e-commerce as well as separate labor forces.

It appears that some use separate technology as well. For instance, among the respondents that used goods-to-person picking systems (roughly a quarter of the survey participants), less than half deployed them for both traditional and e-commerce fulfillment. About a quarter used goods-to-person picking systems solely for traditional fulfillment and another quarter solely for e-fulfillment.

It was a different story, however, when it came to their warehouse management systems. Seventy-one percent of respondents use the same WMS to oversee both e-commerce and traditional fulfillment within the DC.

GETTING THE BIG PICTURE

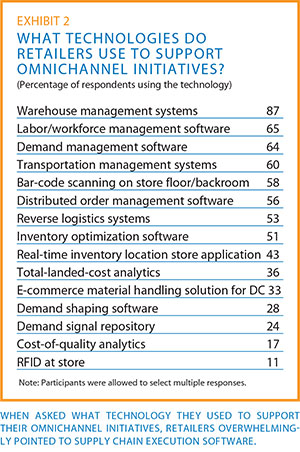

As for what software and technologies the respondents use in their omnichannel distribution operations, most of the survey participants are employing the traditional "supply chain execution" (SCE) applications. These include warehouse management systems, transportation management systems, inventory optimization software, and labor management systems. (See Exhibit 2.)

As for what software and technologies the respondents use in their omnichannel distribution operations, most of the survey participants are employing the traditional "supply chain execution" (SCE) applications. These include warehouse management systems, transportation management systems, inventory optimization software, and labor management systems. (See Exhibit 2.)

But respondents are not limiting themselves to the use of SCE tools. They're using specialized applications as well. For instance, the study found that 64 percent had installed demand management software, which helps companies predict what stock they'll need in their stores and DCs. Another 24 percent were using a demand signal repository to gather information on stocking needs, and, interestingly, 28 percent claimed to be using "demand shaping" software, a sophisticated application designed to stoke buyer interest in products.

Given the popularity of the "common pool of inventory" approach, it was no surprise that many respondents had invested in "distributed order management" (DOM) software, which provides visibility into inventory held in all locations. Fifty-six percent of respondents currently use DOM applications, while 38 percent plan to implement the software.

When it comes to inventory visibility, it's not enough to have the right software. You also need good data—up-to-the-minute information on the precise whereabouts of items. That has proved to be a stumbling block for many operations. Last year's survey found that most companies lacked the technology required to generate accurate data on store inventory.

This year's study indicated companies had made progress in this area. Fifty-eight percent of respondents had deployed bar-code scanners—an essential technology for providing in-store inventory visibility—on the selling floor and in the backroom. Another 43 percent said they had installed a real-time inventory location application for their stores. Still, only 11 percent said they had outfitted their stores with radio-frequency identification technology, which allows for real-time location tracking down to the item level.

LEADERS RELY ON SOFTWARE

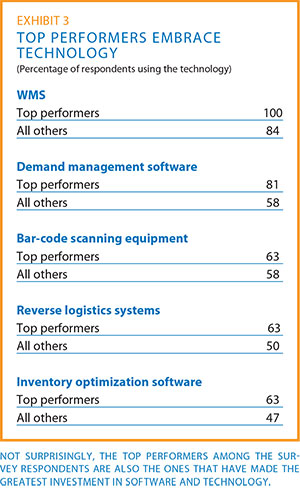

All in all, the study shows that companies have made progress toward building the infrastructure required for omnichannel commerce. But the results also pointed to what could be termed a great techno-divide between the top-performing companies and the rest of the pack. (Top performers were defined as those respondents who self-reported year-over-year revenue growth and 95 percent or better on-time order fulfillment.)

All in all, the study shows that companies have made progress toward building the infrastructure required for omnichannel commerce. But the results also pointed to what could be termed a great techno-divide between the top-performing companies and the rest of the pack. (Top performers were defined as those respondents who self-reported year-over-year revenue growth and 95 percent or better on-time order fulfillment.)

Top performers had invested heavily in sophisticated tools and technology. For instance, 100 percent of the leaders had implemented a WMS to manage their operations, and 81 percent were using demand management software to help determine future inventory needs. They had also invested in bar-code scanning equipment, reverse logistics systems, and inventory optimization software.

It was another story altogether with their less tech-savvy counterparts, which lagged well behind the top performers in a number of categories. (See Exhibit 3.) The failure to invest in technology could cause problems for them down the road. For example, the reliance on paper-based selection methods by many retailers could hamper their efforts to use store inventory to fill online orders. As noted in last year's study, if retailers are to succeed at omnichannel distribution, they'll need to spend the time and money to bring their store fulfillment operations up to par with their DC operations.

For distribution centers, the challenge will be to boost throughput and step up their e-commerce fulfillment game. Although many companies have put in an RF-based WMS, more will have to embrace this technology. So, despite some progress since last year, retailers and manufacturers have their work cut out for them if they want to master omnichannel commerce.

No comments:

Post a Comment