The Supply Circle: How Blockchain Technology Disintermediates the Supply Chain

The supply chain is an outdated structure.

A structure that emerged as the productive model of the industrial age of the nineteenth century. It has become a collection of rusting links, with producers and consumers stuck in obfuscated commodity-driven relationships that keep them both from fully understanding each other’s needs, the needs of the environments they inhabit, and the needs of fair and ethical labor practices. In a rapidly industrializing world, this model was necessary to move products from point A to point B. But it’s been two centuries, shouldn’t we start moving on?

The correct answer: Yes. By utilizing blockchain technology, we can build the necessary internal and external value networks for an entirely new infrastructure for provenance and supply chain management that is transparent, ethically minded, and community driven. The nodes of a value network, which represent resources, are analogous to the nodes on the Ethereum blockchain, in the sense that all come together to build an infrastructure greater than the sum of their parts. The value network supports the independence and deliverables of the larger social ecosystem underlying the supply chain.

Supply Chains Today

Quite simply, a supply chain represents all of the links in the process of getting an item from raw materials to product on a consumer’s shelf. In fashion theory, Lucy Seigle writes, “there are 101 stages in the supply chain, the first being ‘designer attends fabric show’ and the last, ‘order ready for shipment.’” The standard fashion theory supply chain does not even include the processes before the fabric show that turn raw materials like cotton into fabric samples.

In the consumer technology sector, the supply chain would look something like this:

The current supply chain system is in fact so opaque that after research by myself and my colleagues at ConsenSys, we couldn’t find any definable or verifiable information on the supply chains of any major consumer technology company. We have no way of knowing how much slave and child labor, environmental destruction, and violence and political turmoil goes into the production of any of our products, not to mention the actual monetary costs. The consequences of this supply chain mismanagement and fragmentation are evident and dire.

In the case of coltan mining for cell phones, the raw materials directly and indirectly cost the lives of thousands of people in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), where warlords control the coltan ores. Coltan, short for columbite-tantalite, is a black mineral found in large quantities in the DRC, which accounts for 80% of the planet’s coltan. Coltan is used to to create capacitors and is used for everything from cell phones and laptops to jet engines and steel structures like bridges. The control of coltan ores, underpinned by the consumer technology companies that buy from them, allows violent militia groups to have massive power over the population in the eastern part of the DRC.

There are multiple reasons for this, including the appeal of lower prices for multi-national corporations, many US-based, in exchange for inhumane labor practices, as well as sheer ignorance by consumers. Even when consumers aren’t ignorant to the abhorrent costs that go into the products they buy, they either have little to no recourse or, worse, don’t care. Consumer apathy has helped lead us to the state we are in today. This is not the kind of capitalism that we should incentivize.

While entities from the UN, the United States, and others have come together to institute regulations on the Coltan trade and ethical standards, these have been incredibly difficult to implement and carry out. This is due, in part, to the manipulated visibility of the supply chain, leading us to believe that that which is actually invisible (the brokers and subcontractors who produce and sell raw materials, commodities, and labor) is visible.

For example, in 1997, when reports came out that Oregon-based Nike’s subcontractors in Southeast Asia were violating humane labor practices when producing the brand’s famous sneakers, founder and then-CEO and Chairman Phil Knight stated of their first two manufacturers in Japan that “we were 10% of their volume. We actually considered ourselves fortunate that they would make shoes to our design. It never occurred to us that we should dictate what their factory should look like, which really didn’t matter since we had no idea what a shoe factory should look like anyway.”

While Nike has since sought to vastly improve its manufacturing, during the original scandal it was evident that they, as well as other apparel manufacturers named in the scandal, were shifting blame to not only their subcontractors, but also to the relationship between the two. In other words, because the links in their supply chain, from raw materials to manufacturing subcontractors (of raw materials into fabrics) to brokers to other subcontractors (who put together the piece) to the apparel company and finally to retail stores and consumers, are so distant, these companies claimed they could perform no oversight over the conditions of production.

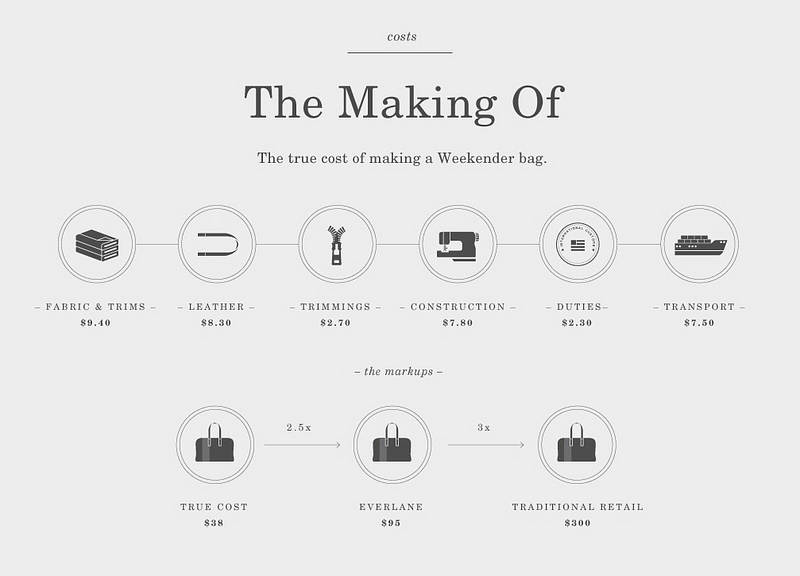

Furthermore, many claimed that this particular supply chain process was necessary to keep costs, and by extension prices, low. Dissimilarly, what this supply chain infrastructure actually does is hide from producers and consumers the costs and human relationships that go into production and consumption. There are companies trying to do the supply chain right, including San Francisco-based fashion start-up Everlane, which visualizes their supply chains and seeks to transparently present the factories to which they subcontract their manufacturing. Below is a chart they released to demonstrate the supply chain of their Weekender bag:

However, many ethically minded companies, including Everlane, could improve the transparency and verifiability of their supply chains by utilizing blockchain technology.

Supply Chains and Commodity Fetishism

As we have seen, the current supply chain structure obfuscates the processes, means, and costs, on all levels, of production from the actual value of products and services. In economic theory terms, this is what Marx referred to as the fetishism of the commodity in the first volume of Capital: Critique of Political Economy. Simply put, Marx theorized that modern economies consider commodities to be things in and of themselves independent of their actual material worth. The material worth of a given commodity should be culled from the financial, environmental, and labor costs, as well as the material relationships that go into their production. As is evident in the case of Coltan ores, the costs and relationships that produce a given commodity are central to that object’s existence. For Marx, this meant that one had to consider these costs and relationships in the monetary value (or price) and conceptualization of the thing itself.

However, this isn’t what happens in practice today and it is not what happened in practice back in 1867 when Marx wrote Capital. In practice, commodities are fetishized as soon as they are produced as commodities, in that their market value is abstracted from the means of production. This a problem because not only are the conditions of production then hidden from us, or willfully ignored by us, the prices we pay for things are not accurate reflections of the multivariate costs of production.

Skipping over the complicated math that Marx utilizes to explain his theory, let’s get to why commodity fetishism matters today, post-Cold War and long after the western Industrial Revolution. As globalisation has made our economies increasingly both fragmented and interconnected, we have seen how the larger consequences of our economic actions have become obfuscated. These consequences include deteriorating environmental conditions and global warming, abhorrent working conditions and even the exploitation of modern slave labor, and prices being inaccurate representations of the costs of production. The urgency to reconsider how our individual, community, and organizational actions affect in the global economy is evident now more than ever.

Blockchain and the Supply Circle

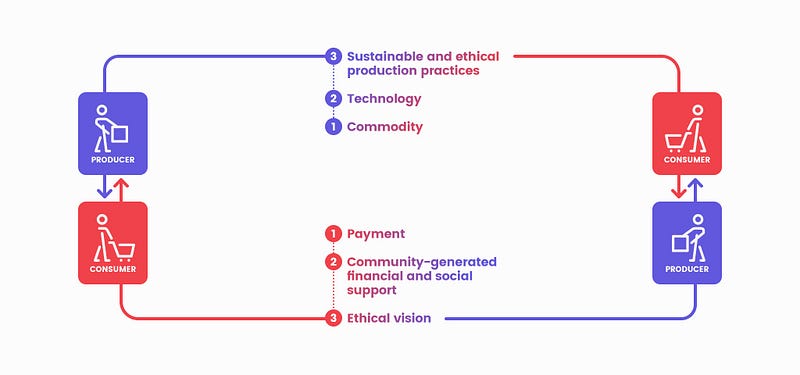

Alternatively, let’s suggest the supply circle. The supply circle might be thought of as a production and consumption system that engages consumers directly in the processes that bring everything from shirts to apples across communities and the globe. Rather than focusing on bringing chicken from the US to Mexico or vice versa in the case of avocados, the supply circle incentivizes community members and local food producers to organize an ethical food system based on cooperation and collaboration. In this instance, community members and farmers both become prosumers, consumers who are also producers depending on their vantage point.

For example, a group of community members who are consumers of apples from a certain farm could also be producers of both payments (in the form of dollars or cryptocurrency), as well as of community-driven grant programs to support local farms. It could look something like this:

A Local, Sustainable Food Supply Circle on the Blockchain

In the case of food, the mismanagement of the supply chain and over-industrialization has caused vast swathes of major urban areas to become food deserts, areas where finding fresh and affordable produce is almost impossible. These are often low-income neighborhoods, where the rapid spread of gentrification is further pushing long-term residents to the brink and accessibility of resources only appears after they’ve been squeezed out of their neighborhoods to areas that are increasingly under-resourced.

Imagine the alternative: an entirely local food system. The seasonal vegetables, produced sustainably and organically, that a mother of two picked up at a greenmarket stand in the South Bronx came from a farmer in the Hudson valley. She may not know his name, but does have his information, as well as the entire life history of her produce in an easily-accessible mobile decentralized application (DApp). She didn’t have to subscribe to a costly CSA or travel miles to find local, fresh food at a price she could afford. Rather, over the past several months, she and her fellow community members have engaged directly with regional farmers, local community gardens, and neighborhood vendors to incentivize and subsidize the collective structuring of a food system.

Concomitantly, a class of elementary school students has begun experimenting with urban farming in East New York, Brooklyn. Through a community partnership with a locally based aeroponic farming organization, they can have a vertical farm installed on the school’s rooftop. Over the season, they will be able to organically and sustainably grow a selection of vegetables and potentially host a community garden event at the end of the season to educate community and network members about the various opportunities for and capabilities of urban farming.

The mother in the South Bronx and the elementary school children have become prosumers, consumers who are also producers. By utilizing smart contracts, as well as core tools like uPort, EtherLoan, and BoardRoom, we can build the software infrastructure that supports this local ecosystem. Imagine logging into a decentralized application, built on top of the Ethereum blockchain, that allows you to look at the individual and organizational identities of farmers and prosumers by utilizing uPort, collectively organize and govern your economic community, and make financial decisions, such as community-sponsored grants to offset seasonal start-up costs for farms, and incentivize sustainable practices and processes that could dramatically lower the price of locally produced food.

Within ConsenSys, the INFLEKT platform is currently building parts of this infrastructure for an agricultural community in Sullivan County. The Inflekt Resource Bank allows for community members of local economies to exchange their time, skills, resources, and products without relying on third parties.

In an ideal system, we may get to a point where the urban farm and food system is completely decentralized. One neighbor may grow strawberries in his rooftop farm, while another grows mushrooms in his. Once every two weeks, they meet in the lobby of their building to exchange portions of their respective yields. Imagine this in distinction to the current food infrastructure, where freighters carry bananas across continents to the shelf of a supermarket. These kinds of exchanges begin to occur across the globe and revolutionize not only how we think of food production, but access to fresh, sustainable and organic food for billions of people worldwide without overextending the environment.

Of course, this isn’t possible only because of software and social infrastructure. Massive breakthroughs in sustainable agrotech, such as aero- and aqua-ponic farming, provide the hardware infrastructure. Blockchain technology allows us to verify not only the origins of a given food product, but also ensure everything from the identities of producers and methods of production to the health and history of the soil (or air or water) a piece of produce was grown in.

Beyond Locality

The supply circle is not only applicable to the local food community. Rather, through the utilization of the blockchain, as well as tracking technologies such as radio-frequency identification (RFID) chips, it is possible to take global production chains and make them remotely visible. Furthermore, the merging of consumer and producer, creating the prosumer, would be centered through both local and distributed community-governed supply circles, with community being defined by each vertical.

Thus, the supply circle on the blockchain could significantly improve upon the already existing goals and priorities of community and corporations alike to become a standard in local and global marketplaces. In utilizing identity and reputation protocols, payments and financial tools, such as lending, as well as smart contract supported governance, to underpin the supply circle, prosumers are incentivized to behave ethically and sustainably and rewarded for their practices.

by Rebecca Migirov, Head of Communications at ConsenSys

No comments:

Post a Comment