Over the course of 18 months, Associated Press journalists located men held in cages, tracked ships and stalked refrigerated trucks to expose the abusive practices of the fishing industry in Southeast Asia. The reporters’ dogged effort led to the release of more than 2,000 slaves and traced the seafood they caught to supermarkets and pet food providers across the U.S. For this investigation, AP won the 2016 Pulitzer Prize for Public Service.

Below is an excerpt from the AP ebook, FISHERMEN SLAVES: Human Trafficking and the Seafood We Eat:

For hundreds of slaves, Benjina was the end of the world.

The remote Indonesian island village was cut off for several months a year due to stormy seas. There were no roads or telephone service and just a few hours of electricity a day.

The Burmese fishermen who docked here spent months at sea, pulling up monstrous nets and sorting seafood around the clock. But the relief they felt after touching land was quickly replaced by desperation. They were trapped, held captive by Thai boat captains working for large fishing companies. Some men were locked in a cage for simply asking to go home. Others who managed to run away were stuck on the island, living off the land for a decade or longer. And just off a beach, a jungle-covered graveyard was crammed with the corpses of friends and strangers buried under false names.

When AP reporters first arrived in Benjina in late November 2014, informing the men we were there to tell their stories, they couldn’t believe it. A few wiped away tears as they spoke. Some chased after us on dusty paths, shoving pieces of paper into our hands with the names and addresses of their parents in Myanmar.

“Please,” they begged. “Just tell them we’re alive.”

- In this Monday, April 6, 2015 photo, former fishing slave Kyaw Naing pauses during an interview with the Associated Press in Jakarta, Indonesia. Kyaw Naing, who was at one point kept in a cage on the remote island of Benjina, is among eight migrant fishermen rescued for their safety in the course of an Associated Press investigation into slavery in the seafood industry. Hundreds of others evacuated by the Indonesian government after the story are waiting to be repatriated. (AP Photo/Dita Alangkara)

- Fishing boats carrying recently rescued fishermen sail toward the town of Tual, Indonesia, Saturday, April 4, 2015. The rescued fishermen were among hundreds of migrant workers revealed in an Associated Press investigation to have been lured or tricked into leaving their countries and were brought to Indonesia to be forced to catch seafood. (AP Photo/Dita Alangkara)

The long, sometimes dangerous, journey of telling the story of Southeast Asian men held captive on fishing trawlers began in late 2013.

Human trafficking in the global seafood industry had been written about anecdotally, but Associated Press reporters Robin McDowell and Margie Mason were determined to connect the dots in a way that would make the world finally take notice.

Their best bet, they decided, would be to link slave-caught fish to American dinner tables _ and name names. At the start, sources told them it would be next to impossible. The industry was huge, and its practices murky. Fish was transferred between boats at sea. Documentation on land was often done improperly. And tainted and ‘clean’ seafood was mixed together at huge export markets.

- In this Saturday, Nov. 22, 2014 photo, workers in Benjina, Indonesia, load fish into a cargo ship bound for Thailand. Seafood caught by slaves mixes in with other fish at a number of sites in Thailand, including processing plants. U.S. Customs records show that several of those Thai factories ship to the United States. (AP Photo/Dita Alangkara)

Nearly a year into their investigation, they caught a major break. A source pointed them to eastern Indonesia, where they discovered a slave island.

At great risk, McDowell, with the help of Burmese reporter Esther Htusan, filmed a man in a cage, and others pleading for help over the side of their giant trawler. The two also watched as fish was loaded onto a giant refrigerated cargo ship, and then tracked it by satellite to a Thai harbor. They were there with Mason to meet it in trucks, following the catch over several nights through the seedy, mafia-run streets. California-based reporter Martha Mendoza then joined forces to complete the four-woman team, eventually linking the seafood directly to U.S. supermarket chains and retailers, including Wal-Mart and Kroger.

The story captured worldwide attention. It led to governmental and corporate action. More importantly, it resulted in one of the biggest rescues of modern-day fishing slaves, with more than 2,000 men from four countries being identified and repatriated, some returning to homes they hadn’t seen in 20 years.

- In this July 17, 2015 photo, DigitalGlobe imagery analyst Micah Farfour, shows a high-resolution satellite photograph taken of trawlers in Papua New Guinea loading slave-caught seafood onto Silver Sea 2, a refrigerated cargo ship belonging to the Thai-owned Silver Sea Fishery Co., at DigitalGlobe’s headquarters in Westminster, Colo. Authorities in Papua New Guinea have rescued eight fishermen held on board a Thai-owned refrigerated cargo ship, and dozens of other boats are still being sought in response to an Associated Press report that included satellite photos and locations of slave vessels at sea. (AP Photo/Brennan Linsley)

- In this Nov. 2014, photo, a security guard talks to detainees inside a cell at the compound of a fishing company in Benjina, Indonesia. The imprisoned men were considered slaves who might run away. They said they lived on a few bites of rice and curry a day in a space barely big enough to lie down, stuck until the next trawler forces them back to sea. In its first report on trafficking around the world, the U.S. criticized Thailand as a hub for labor abuse. Yet 14 years later, seafood caught by slaves on Thai boats is still slipping into the supply chains of major American stores and supermarkets. (AP Photo/Dita Alangkara)

- In this Friday, Dec. 12, 2014 photo, Min Min, from Myanmar, rests on a make-shift bed. Min Min was rescued from a tiny island two months ago, on the verge of starvation, and brought back to Thailand, the world’s third-largest seafood exporter. Concerns about labor abuses, especially at sea, prompted the U.S. State Department last year to downgrade Thailand to the lowest level in its annual human trafficking report, putting the country on par with North Korea, Iran and Syria. (AP Photo/Wong Maye-E)

Slave-caught fish and U.S. tables: Making the connection

Each small factory that accepted one of the loads of slave-caught fish raised the question, where does it go next? Pulitzer Prize-winning reporter Mendoza went to work. Her account:

We spent weeks calling distributors, processors, freezers, and visiting Thailand’s largest fish market and talking to security guards and workers to obtain information that linked them to large Thai seafood export businesses.

In California, I began a search of my own, looking through U.S. Customs records to trace the seafood directly to companies familiar to most Americans.

Plugging away at databases that track U.S. imports, I checked to see whether the companies receiving the tainted fish in Thailand were shipping to a U.S. distributor, and whether those deliveries were packaged and branded.

- In this Dec. 10, 201 photo, two refrigerated cargo ships, the Silver Sea 2, background, and the Silver Sea Line, foreground, are docked at Thajeen Port in Samut Sakhon, Thailand. The European Union is maintaining the threat of a seafood import ban on Thailand because the global exporter is still not doing enough to improve its fisheries and labor practices, officials said Thursday April 21, 2016. (AP Photo/Wong Maye-E)

- Navy personnel stand guard as the crew of Silver Sea 2, a Thai-owned cargo ship which was seized by Indonesian authorities last August, are lined up during a media conference at the port of Sabang, Aceh province, Indonesia, Friday, Sept. 25, 2015. The Thai captain of the ship has been arrested in Indonesia following allegations of illegal fishing, an official said Friday. It is the latest development linked to an Associated Press investigation that uncovered a slave island earlier this year. (AP Photo/Heri Juanda)

It was relatively easy to determine that cans of cat food labeled Fancy Feast, Meow Mix and Iams came out of Thai processors that bought fish off the boat from Benjina. But the U.S. distributors were more complicated because they are not required to disclose where they sell fish. Thus began my odyssey to dozens of supermarkets in different states to check out frozen and canned seafood. Was it from Thailand? Was it a species we had seen? What brand was it? Who was the distributor? Then it was back to the databases for a potential match.

This became part of my daily life for weeks. I even took my husband on a date night to a local Wal-Mart to search for seafood. One day, driving home from my daughter’s field trip, I pulled into another Wal-Mart, sending out an army of fifth-graders to examine bags of frozen fish and filling my iPhone with photos of labels. On weekends, Mason and I swapped snapshots as we grocery shopped, a continent away from one another.

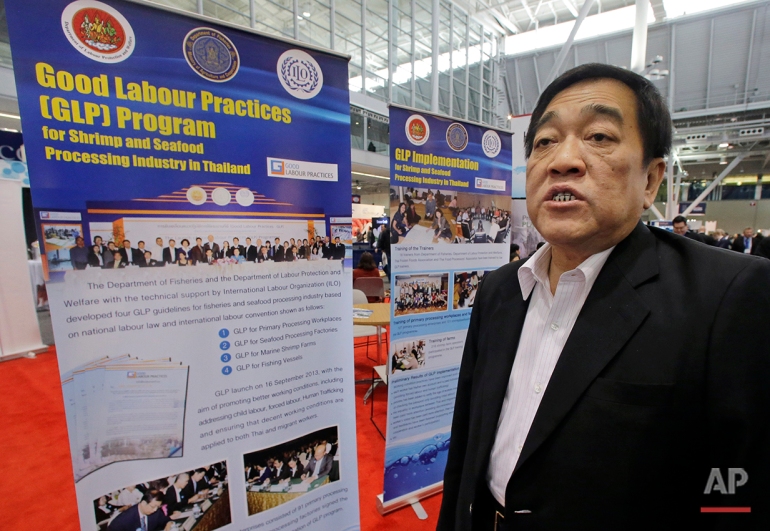

Eventually, the puzzle came together. With weeks of database tracking, we found seafood from Benjina in the supply chains of supermarkets, distribution centers and restaurants in every state at thousands of outlets. And then, with a videographer and photographer, I headed to Boston for the North American Seafood Expo to talk to companies with tainted supply chains, industry groups and Thai and Indonesian representatives.

- A worker shows a shark during an inspection by Indonesian fisheries officials inside the cold storage room of Pusaka Benjina Resources fishing company in Benjina, Aru Islands, Indonesia, Thursday, April 2, 2015. Officials from three countries are traveling to a remote island of Indonesia to investigate how thousands of foreign fishermen wound up there as slaves and were forced to catch seafood that could eventually end up being exported to the United States and elsewhere. (AP Photo/Dita Alangkara)

- In this Monday, March 16, 2015 photo, Thai Frozen Foods Association President Dr. Poj Aramwattananont speaks during an interview at the Seafood Expo in Boston. He said Thais know that human trafficking is wrong, but Thai companies cannot always track down the origins of their fish and whether it is “good or bad.” (AP Photo/Elise Amendola)

The National Fisheries Institute, in a pre-emptive strike, sent a warning to the companies at the show: “Prepare for major AP story on labor abuse in seafood: Association advises members Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist reporting from Boston show floor.”

The warning had an impact. We were followed by men, apparently working for seafood firms, as we worked the floor. Salespeople turned their backs. When we were told to come back later, we simply sat down and waited, sometimes for hours.

Eventually we had given all the subjects of our story an opportunity to respond, and obtained comment on camera from Thai and Indonesian authorities. We were ready to publish.

But there was still one major obstacle left. The men on Benjina identified by name, in photos or in video were vulnerable. And we couldn’t run the story until their safety was guaranteed.

- Burmese fishermen wait for their departure to leave the compound of Pusaka Benjina Resources fishing company in Benjina, Aru Islands, Indonesia, Friday, April 3, 2015. Hundreds of foreign fishermen on Friday rushed at the chance to be rescued from the isolated island where an Associated Press report revealed slavery runs rampant in the industry. Indonesian officials investigating abuses offered to take them out of concern for the men’s safety. (AP Photo/Dita Alangkara)

- In this April 3, 2015 photo, Burmese fishermen prepare to board a boat during a rescue operation at the compound of Pusaka Benjina Resources fishing company in Benjina, Aru Islands, Indonesia. On Thursday, March 10, 2016, five Thai fishing boat captains and three Indonesians were sentenced to three years in jail for human trafficking in connection with slavery in the seafood industry. The suspects were arrested in the remote island village of Benjina in May 2015 after the abuse was revealed by The Associated Press in a report two months earlier. (AP Photo/Dita Alangkara)

Twenty-two years a slave: One man’s story

After interviewing dozens of rescued slaves, Mason found one with an extraordinary story. She followed him from the island of Tual, Indonesia, where all of the freed slaves were temporarily housed, to his home in Myanmar. Here is her account:

- In this May 15, 2015, photo, Myint Naing, a former slave fisherman who spent more than two decades in Indonesia after being enslaved on Thai fishing boats, rests at a government hostel in Yangon, Myanmar after returning to his home country the day before. Myint, 40, is among hundreds of former slave fishermen who returned to Myanmar following an Associated Press investigation into the use of forced labor in Southeast Asia’s seafood industry. (AP Photo/Gemunu Amarasinghe)

- In this May 16, 2015, photo, former slave fisherman Myint Naing, center, and sister Mawli Than, left, are overcome with emotion as they are reunited after 22 years at their village in Mon State, Myanmar. Myint, 40, is among hundreds of former slave fishermen who returned to Myanmar following an Associated Press investigation into the use of forced labor in Southeast Asia’s seafood industry. (AP Photo/Gemunu Amarasinghe)

I couldn’t believe it when I met Myint Naing in Tual. He told me he had been in Indonesia since being trafficked in 1993, the year I graduated high school.

He pulled back the hair on top of his head to show me a jagged scar, telling me his skull had been cracked by one of his bosses, simply for asking if he could go home. Later, he asked a second time, and was shackled to his boat with no food or water and told he would be killed. He managed to escape one night and swam to shore. He then hid in the jungle with help from a local family for years.

Myint boarded the first of four planes that took the former slaves back to Myanmar. When he arrived at the biggest city, Yangon, I was there with a team of AP reporters to meet him. We followed him as he boarded an overnight bus with other men from Mon State, and then in a car that took him to the village he’d left behind 22 years ago.

- In this May 16, 2015, photo, former slave fisherman Myint Naing, left, is embraced by his mother Khin Than, second left, as his sister Mawli Than, right, is overcome with emotion after they were reunited after 22 years in their village in Mon State, Myanmar. Myint, 40, is among hundreds of former slave fishermen who returned to Myanmar following an Associated Press investigation into the use of forced labor in Southeast Asia’s seafood industry. (AP Photo/Gemunu Amarasinghe)

As Myint leaped from the vehicle, we watched what could have been a scene from a movie. First, Myint embraced his sobbing baby sister. Then, a small, frail figure ran toward him. He wailed and then fell to the ground before he was pulled into his mother’s arms.

Htusan and I hugged on the side of the road as we were overcome. This was the true power of journalism, and we all knew it was happening over and over in villages across Southeast Asia. It was amazing to see, but even more amazing because we helped make it happen.

The investigation continues: More to come

AP’s work on the story is unfinished. The release of the first slaves was followed by a four-month quest, using satellites and sources, to find men the reporters knew were still enslaved at sea after their boats fled Benjina.

Nearly two years into the investigation, the impossible question has clearly been answered: thousands of enslaved men have been forced to fish, catching seafood that ends up on U.S. dinner tables. But much more remains to be done. The chance to make a difference is what led us to our profession in the first place, and with the support of the AP, further reporting is already underway.

No comments:

Post a Comment