Why President Trump Does Not Tweet About Automation

"Fully automated trucks could put half of America’s truckers out of a job within a decade..."

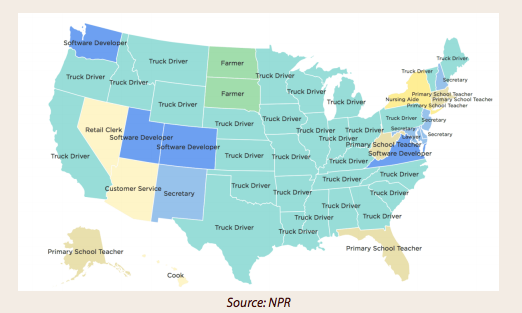

A widely circulated NPR graphic shows “truck driver” was the most common job in more than half of the U.S. states in 2014?—?in part because how the Bureau of Labor Statistics sorts common jobs, such as educators, into small groups. Indeed, truck driving is one of the last jobs standing that affords good pay (median salary for tractor-trailer drivers, $40,206) and does not require a college degree. According to the American Trucking Association, there are 3.5 million professional truck drivers in the U.S. Entire businesses (think restaurants and motels) and hundreds of small communities, supporting an additional 5.2 million people, have been built around serving truckers crisscrossing the nation. That’s 8.7 million trucking-related jobs. It also represents one of Trump’s most important voting blocs?—?working-class men.

But like many of the blue-collar jobs the President promised to save during his campaign, the future of these 3.5 million trucking jobs is less than certain. Fully automated trucks could put half of America’s truckers out of a job within a decade, The Los Angeles Times reported last year. This isn’t an imagined future. It’s already happening. Otto, an automated trucking company acquired by Uber, made a delivery of beer last year and has been approved to travel two routes in Ohio.

Last year, Noel Perry, an analyst at industry research firm FTR Transportation Intelligence, told The International Business Times: “Despite a shortage in high-quality drivers, pay hasn’t gone up in five years. Trucks are easier to drive.” So-called “soft-automation” features, like automatic braking and lane assist, mean the trucks can already be driven by less experienced operators commanding smaller salaries. Even ahead of automation, the profession is losing traction. Perry’s final remark to IBT strikes to the heart of the matter?—?“The free market produces jobs, the government doesn’t.”

Drivers reportedly account for about one third of the cost in the trucking industry. Ostensibly, there isn’t much a president?—?even one as untraditional as Trump?—?can do to stop a company from making more money. Or is there? Which begs the question: How will automation, employment, productivity and Trump co-exist?

A few days after Trump “saved” 750 jobs at Carrier, Greg Hayes, CEO of Carrier’s parent firm, United Technologies, admitted that automation would eventually win out. During a CNBC interview with Jim Cramer, Hayes revealed: “We’re going to make a $16 million investment in the factory in Indianapolis to automate to drive down costs so that we can continue to be competitive. . .But what that ultimately means is there will be fewer jobs.

Thomas H. Davenport, professor in management and information technology at Babson College, opined recently for The Harvard Business Review:

“Trump knows virtually nothing about technology?—?other than a smartphone, he doesn’t use it much. And the industries he’s worked in?—?construction, real estate, hotels, and resorts?—?are among the least sophisticated in their use of information technology. So he’s not well equipped to understand the dynamics of automation-driven job loss.“. . .The Art of the Deal’s author clearly has a penchant for sparring with opponents in highly visible negotiations. But automation-related job loss is difficult to negotiate about. It’s the silent killer of human labor, eliminating job after job over a period of time. Jobs often disappear through attrition. There are no visible plant closings to respond to, no press releases by foreign rivals to counter. It’s a complex subject that doesn’t lend itself to TV sound bites or tweets.To be fair, it’s not just Trump who finds this a difficult enemy to battle; other politicians don’t engage with that much either. And there are several good reasons. . . One is that automation usually comes with corporate investment rather than cutbacks. Note that United Technologies announced a $16 million investment in the Indiana Carrier plant. Who wants to criticize that?”

As we have written, Trump’s number one priority is to get re-elected. To do so, he will have to keep the 8.7 million men and women in the trucking sector employed. At the same time, he has pledged to encourage foreign investment in the U.S. and to attract U.S. companies back to American soil, all with an eye to creating more jobs for Americans. To remain competitive, these companies will have to improve productivity, and the shortest path to increased productivity, is automation. But, even with vigorous training, the vast majority of America’s working middle-class, like the 3.5 million truckers who voted largely for Trump, cannot transition easily into the types of job created by automation?—?engineering, integration, IT.

Therein lies the dilemma facing America, and much of the developed and the developing world. The economy needs more productivity growth, not less. But it also needs to create jobs. Any politician who wants to appeal to the business community will be reluctant to provoke a war against automation. But, he cannot afford to see his key voter bloc displaced.

All of which begs the question: How can Trump insulate the status quo from the disruptive forces of automation and technology? Will he tweet to the perception or the underlying reality?

No comments:

Post a Comment