Target’s Future Will Be Decided by Kids

The retailer is rebooting its children’s lines in an attempt to regain its former cool.

Photographer: Ackerman and Gruber

Mini taste arbiters select favorites at Target’s head office.

Marquan Harper arrived at the Minneapolis head office of Target dressed as if he were coming to work. The St. Paul 10-year-old had approximated the store uniform—a red shirt and khaki pants—and persuaded his mom to do the same. He checked in at reception, put on his lanyard, and joined 16 other kids to weigh in on a new line of children’s and babies’ clothes called Cat & Jack.

The group, demographically correct and temperamentally diverse, piled into Room 445, transformed for the day into a giant walk-in closet the kids could ransack. They styled one headless, child-size mannequin in a striped neon dress and brown suede boots and another in blue leggings, blue suede boots, and a gray T-shirt that read “Inventor.” With its playful layers, boho-chic cuts, and muted shades juxtaposed with hits of neon, Cat & Jack looks a lot like Crewcuts, J.Crew’s adventurous line for young fashion plates (or their aspirational parents). New for Target is a focus on graphic T-shirts with feel-good contemporary slogans such as “Change the World by Being You.”

Marquan says he’s mostly outgrown graphic tees, though he might wear one when he records gaming videos for his YouTube channel, as long as the shirt doesn’t seem braggy. Finnegan Wambay, also 10 and from Chicago, is more receptive: “My favorite T-shirt here is ‘Periodically Genius, But Always Cool,’ ” he says. “I would wear that every day.”

Featured in Bloomberg Businessweek, July 11 - 17, 2016. Photographer: Steven Brahms for Bloomberg Businessweek. Styling: Mariah Walker/Art Department; Props: Amy Henry/Brydges MacKinney. Dress: Zoe LTD; Shoes & cardigan: Zara

Anybody who’s been around young families knows that parents solicit their kids’ opinions about all kinds of once-adult decisions: where to go for dinner, what kind of car to buy, even what to wear. In keeping with the times, Target’s designers have been listening to kids, too, about 1,000 of them from the ages of 4 to 12—in their homes, online, at daylong fairs, and in focus groups—to create what could become one of the company’s biggest brands and maybe one of the country’s biggest kids’ brands.

For two decades, Target’s two mainstay kids’ labels were Cherokee and Circo. These togs were noteworthy for their ordinariness, as easy to throw in the shopping cart as granola bars or juice boxes, and for how consistently they sold, accounting for roughly a billion dollars a year in sales. Now, Target is taking what amounts to a great leap of faith for a lumbering, 1,800-store retailer: throwing out what’s worked and opening its sales to the winds of trends and the whims of children.

Cat & Jack is a crucial step in a long-term plan to revitalize Target, the second-largest discount retailer in the U.S. Executives are funneling their attention and resources into four broad areas—babies, kids, style, and wellness. These signature categories, as they call them, account for $25 billion in annual sales, one-third of the company total, and have higher margins than essentials such as groceries and appliances. Once reimagined, these areas are expected to generate sales that will grow two to three times faster than the store’s other staples.

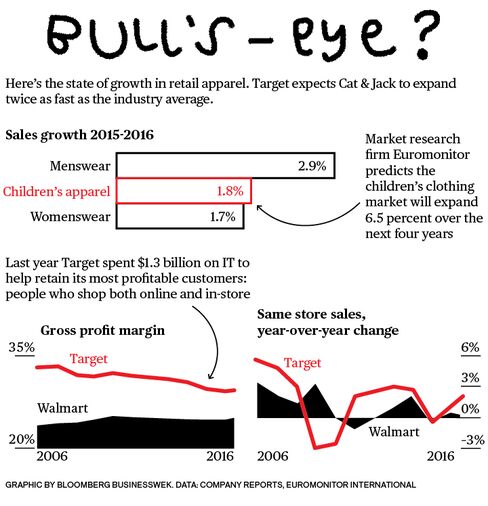

When Cat & Jack replaces Circo and Cherokee in mid-July, Target executives will need these (somewhat) groovier cuts and colors to continue to appeal to already satisfied customers. They’re also betting that sales will increase at twice the rate of children’s lines at such competitors as Walmart Stores, Kohl’s, the Children’s Place, and Old Navy. But enthusiasm for Cat & Jack goes deeper than the bottom line. Target has thrown money, time, and reams of research into tutu dresses and dancing robot shirts because the company’s future is supposed to look the way Cat & Jack is supposed to look: optimistic, modern, wholesome, inclusive, fun. That’s a lot like what people thought of Target before it lost its cool.

For years, Target had pulled off a feat that made it the envy of retailers and “Tar-zhay” to its customers. It sold high design at low prices and gave big-box shopping some luster. Remember? In 1999 the architect Michael Graves introduced his witty postmodernism to the masses there. His stainless-steel teapots capped with a whistling bird for Alessi usually sold for $100; Target’s version, with an actual whistle in lieu of a bird, went for $39.99. Isaac Mizrahi designed clothes not only for Bergdorf Goodman, but also for Target. Long before H&M, Target galvanized the designer collaboration craze, selling limited-edition collections from Jason Wu, Rodarte, Proenza Schouler, and Missoni. To draw in high-minded and deeper-pocketed shoppers, it bought up all the ads in an issue of the New Yorker. In 2005 it staged a fashion show in New York where gymnasts rappelled down the face of 30 Rockefeller Center. The chain’s mascot, Bullseye, an English bull terrier, is in Madame Tussauds wax museum.

Target came into being in 1962, the same year as Walmart and Kmart. Walmart claimed global domination, Kmart puttered along, and Target became the standard-bearer for cheap chic. Its clever marketing campaigns—“Hello Good Buy,” a Beatles song remake, is one of the most memorable—made people feel better about shopping there instead of Walmart for essentials, even if the products sometimes cost more. Necessities, such as Method, the minimalist housecleaning products that distinguish Target’s fluorescent-lit shelves from its competitors’, account for almost half of its revenue. “Target was the world’s best-merchandised discount store,” says Howard Davidowitz, who runs a retail consulting firm in New York.

As consumers traded down during the recession, Target did too. It focused on lower-priced, lower-quality goods rather than the high-concept clothes, teapots, and garlic presses it was known for. That decision brought it more directly in competition with Walmart, dollar stores, and Amazon.com. Trying to out-cheap them in a low-margin business proved a losing proposition.

In 2008 sales at existing stores fell 2.9 percent for the year, the first decline in at least three decades. After another bad year, sales slowly improved until December 2013, when news surfaced that hackers had stolen the credit card or personal information of some 70 million customers. Holiday profit was almost halved, and the breach eventually cost the retailer $200 million and singed its faltering reputation. That same year the company ventured outside the U.S. for the first time, opening stores in Canada at second-rate locations vacated by a failed discounter and stocking them with merchandise priced higher than in its U.S. stores. Huffington Post Canada reported to resentful locals that, for example, a set of two Riedel Vivant Pinot Noir Tumblers sold for C$24.99 (about $24 in 2013) but were listed at $19.99 on Target’s U.S. website. Then, a new distribution system introduced there broke down, leaving warehouses full and shelves empty.

The situation had become desperate enough that the board of directors hired the first outsider to run Target in its 52-year history. When Brian Cornell, formerly a senior executive at PepsiCo and head of Sam’s Club, became chief executive officer in August 2014, his first major decision was to shut down the Canadian operation; the company took a $5.4 billion writedown. (Former CEO Gregg Steinhafel had told Women’s Wear Daily in June 2012 that he expected “Target Canada to deliver $6 billion or more in sales and 80¢ or more in earnings per share by 2017.”)

Perhaps the biggest issue was that under Steinhafel, the once groundbreaking retailer had become bureaucratic and insular while the industry had become hypercompetitive. Target didn’t take online shopping seriously, missing out on the emergence of the millennial shopper and the mighty swing to e-commerce. Amy Koo, an analyst at Kantar Retail, says the percentage of U.S. families at the end of 2007 who had shopped at a Target within the past month was 53.2 percent, vs. 31 percent in May.

Executives say they’re through the worst and agree on how to talk about the dark years. They start with their slogan “Expect More. Pay Less.” “We pulled back on the ‘expect more’ and focused on the ‘pay less,’ ” Cornell says. “As soon as we uncouple that idea, we’re no longer Target,” says Jeff Jones, the chief marketing officer. “There are lots of places where you can pay less and lots where you can expect more.” Target had become neither.

“We had lost some of our edge,” Cornell says. “We had to modernize.” Target also had to downsize: It’s let go 2,600 people and eliminated an additional 1,400 open positions, reducing its staff at headquarters by 30 percent. Of Cornell’s 12 senior executives, nine are new to the company or to their job.

Cornell is trim and compact, holds an iPad on his lap, and wears a crisp, blue-checked shirt and blue suit pants, an outfit that would’ve violated the previous coat-and-tie executive dress code. Target was always a more conventional company than its savvy design and ad campaigns suggested. These days, everyone at the office can wear jeans and T-shirts.

Cornell likes to give interviews on the 26th floor, a bright, airy space where the design team displays its favorite products, such as a marble tea-candle holder and a bedsheet with a pocket for a mobile phone. He roams around, eats at the company cafe, and sometimes conducts impromptu in-store focus groups. He regularly invites executives from modish tech companies such as Pinterest and Snapchat to give talks.

In meetings early on, Cornell says, he had to encourage “more conversation, fewer slides.” He asked staff to call out problems in areas other than their own. “It is sometimes uncomfortable. We’re a Midwestern company. We didn’t say the hard things before,” says Joshua Thomas, a spokesman.

Consider that until two years ago Target didn’t use mannequins or that until this year it didn’t have visual merchandisers, the group of creatives devoted to store displays. Executives didn’t think they needed either. Even when they were at their best, Target’s stores never quite lived up to the expectations of those coming for the designer “collabo” products which were often sitting forlornly between plastic tumblers and jumbo pretzel bags. The thrifty approach served to keep budget-minded customers from feeling alienated, but now that Whole Foods Market makes even lettuce look lush and H&M has introduced the velvet rope to discounters, Target has to step up.

Executives are pleased to report that clothes displayed on mannequins sell 30 percent more than when they’re on racks or shelves. Even in downtown Brooklyn at Target’s busiest, and often messiest, store, the mannequins are dressed neatly in red, white, and blue before the July 4 holiday. One is wearing a Cherokee red tulle miniskirt, a navy vest with ice pops, and a navy T-shirt. Another has stars-and-stripes leggings and a blue T-shirt emblazoned with a map of America. Although the rest of the girls’ department is subjected to fluorescent lighting, there’s track lighting above the mannequins. It helps.

“They could add more fashion, more dresses.”—Hailey Bauman, 7

Photographer: Ackerman and Gruber

Target is also redesigning the front area of its stores, aka the Bullseye Playground. Before, shelves there looked like bargain bins—with three-ring binders, socks, math flash cards, jute twine, and marshmallow skewers jumbled together—although bargain bins that brought in more than half a billion dollars a year. Most items are still less than $7, but the shelves are streamlined and cheerier. In one Minneapolis store in late May, LED string lights, candles, American flags, paper lanterns, tote bags, and seed kits are lined up in their proper spots, their prices easy to see. Sales have increased 30 percent.

Target’s typical customer is changing, too. Executives used to describe her (always her) as a boomer mom who drives a minivan and lives in the suburbs. Now, Target says it has more Hispanic, millennial, and urban shoppers. Which is why it ran ads featuring Hispanic celebrities during the Billboard Latin Music Awards, created its Cartwheel app to offer special deals, and plans to open two stores in New York City this year.

All families shop for kids’ clothes, though, making it one of the most reliable categories for retailers. It’s a $30 billion market in the U.S. that grew 1.8 percent last year, split among such companies as Children’s Place, Gap, Gymboree, H&M, Kohl’s, Walmart, Zara, and many small boutiques, some online only, according to Euromonitor International. “The good thing about the kids’ business is that it is a little more stable” than women’s and menswear, says Susan Anderson, an analyst at FBR Capital Markets. Because growth in the kids’ clothing business is modest, “it’s really just a battle for market share,” she says. Target is second to Walmart among the mass merchants, which together account for about 40 percent of children’s apparel sales, according to market researcher NPD Group.

Target's Bet on 10-Year-Old Fashionistas

Amanda Nusz is Target’s head merchant for kids’ clothes and Nadine Steklenski is head designer. They’ve worked together for almost 10 years and really do finish each other’s sentences. Whatever tension exists between them as they balance taking risks and making the numbers, they’re equally adept at hiding it. They’re both energetic, though Steklenski, in a tight black dress with a faux-leopard coat and a big, turquoise necklace, is the more boisterous. Nusz wears a white lacy shirt from Adam Lippes for Target and pants from Target’s Merona brand. While everyone else labors in typical cubical farms, the 270 designers work in an open space with art studios, glass-walled showrooms, lots of natural light, and even two balconies where they can enjoy the brief Minneapolis summer.

Nusz and Steklenski say they’d been eager to try something different for kids but could never persuade Steinhafel to back them. Early on, Cornell said he wanted Target to be “famous for kids.” Nusz and Steklenski argued for scrapping Circo, the in-house kids’ brand; ending the licensing agreement with Cherokee, which Target designs; and creating a line for newborns to preteens. “That was a big decision, because Circo and Cherokee were successful,” says Julie Guggemos, head of product design and development, who’s been at Target for almost 26 years. “The kids’ business wasn’t broken. It was strong.” It was sort of invisible, though, and hadn’t evolved much from the look of the Olsen twins on Full House. “If you only put hearts and flowers in an assortment for girls and it sells, you think that’s all they want,” Guggemos says. “Girls love science. People know that, but that unfortunately wasn’t the take we had.”

Last year, Target stopped separating toys into boys’ and girls’ aisles. This year it announced that transgender customers could use the bathroom of their choice. Cat & Jack isn’t gender-neutral, but there will be an online-only collection of shirts under the name, Tees for All, with words like “Athlete” or “Smart & Strong” available for boys and girls in a unisex fit. Clothes in the stores will remain separated by gender. Cat & Jack will still offer sparkles and glitter, pink and purple, frills and ruffles, and, at least at some point, kid-size butterfly wings and a long tulle skirt with glow-in-the-dark stars. The prints on Cat & Jack dresses won’t be wildly different from what’s been in stores, but they’ll be more sophisticated, the color combinations less typical. The polka dots will be bigger, the stripes neon. There will be a short-sleeve dress with boldly drawn flowers and leaves on a black background; another dress will have a pale pink sweatshirt on top and an orange tulle skirt. Boys will still get dinosaurs and astronauts on their T-shirts and slouchy pants with drawstring waists.

Cat & Jack is geared for a generation of kids that’s more collaborative than competitive. “They’re not about positivity that makes themselves feel good but someone else feel bad,” says Mandy Daneman, who conducts research for Target. She and her team interviewed hundreds of kids, dug into academic studies, and talked with companies such as Walt Disney and Nickelodeon. “The kids told us: I don’t want shirts that say, ‘I Win, You Lose.’ I want shirts that say, ‘We Got This,’ or, ‘Game On.’ ” The team changed a shirt from “Play to Win” to “Play for Fun.”

Nusz and Steklenski noticed that kids have a finely developed and widely shared sense of humor. “Now it’s cool to be the funny one,” Nusz says. Especially for boys, says Steklenski. “I see boys walk around with unicorns on their shirts—if there are butterflies coming out of the butt.”

“We’re not in the self-esteem business, but we are in the self-expression business,” Nusz says. Adds Daneman: “The kids are saying, ‘I want to stand out in my pack.’ Think about it. That means ‘I want to be unique but not unique enough that I don’t have a place.’ ”

“If I’m going to church. I’ll dress up. If I’m going to a sports event, I’ll wear a jersey.”—Marquan Harper, 10

Photographer: Ackerman and Gruber

Target listens, to a point. Kids change their minds, and parents ultimately pay. That’s why although 10-year-old Finnegan loved the “Periodically Genius, But Always Cool” graphic, the designers changed it, because they mostly heard that kids care more about being smart than cool. Now it’s simply “Genius” written with elements from the periodic table.

When one group of parents and kids saw a boys’ T-shirt with the saying, “Lost in Space—No Wifi Out Here,” the adults thought it was funny and the kids thought that seemed like a very scary place. Nusz decided to keep the shirt in the collection. Then there was the tee with camouflage made of kale. It was a favorite of the designers, but no one else cared for it. The most polarizing shirt said simply, “OMG.” The kids loved it, but “parents don’t really want sass on the T-shirt when they are already dealing with it at home,” Nusz says. They cut it. “If it was going to be our No. 1 seller, we’d have to think about it.”

Target’s design staff used to browse competitors for inspiration. Now, Steklenski says, “I don’t want a derivative of a derivative. Don’t go to Topshop, go to Morocco,” the country that’s the source of the djellaba chic swirling through the pages of Vogue. They went. They drew pictures of the mosaic tiles to create patterns for some of the dresses. They also traveled to Bali to visit the Green School, which says it’s the world’s only completely sustainable school. When talking to the kids about social issues, Target’s merchants and designers thought hunger or homelessness among children would come up. Instead, the kids talked about saving animals. Afterward, the designers went to an aquarium and a zoo; images such as a human with a lion’s head now pop up on the clothes.

Cat & Jack will be more up-to-the-minute than the Circo and Cherokee labels, but the clothes have to cost the same, from $4.50 to $39.99. Executives also want to highlight Target’s one-year guarantee on its own brands of clothes; no surprise that the promise tested well with everyone, especially, they say, Hispanic customers.

To make the math work, Target is signing longer-term contracts with its apparel suppliers, which are concentrated in Bangladesh, Cambodia, China, and Indonesia. Nusz and Steklenski introduced suppliers to Cat & Jack early in the design process and solicited ideas for materials, such as one they’re calling Tough Cotton, a cotton-and-spandex blend softened by a chemical that Steklenski claims is safe enough to drink and makes the cotton fibers stronger with every wash. “And we have tough negotiation tactics,” Guggemos says. Target, like other price-conscious retailers, requires its suppliers to justify every cost for every item each year, rather than start with the budget from the prior year. The new executive in charge of the supply chain is Arthur Valdez, who used to work at Amazon.

“Target is operating at the low end of the market, and they put pressure on the contract manufacturers to reduce cost by any available means,” says Scott Nova, executive director of the Workers Rights Consortium. “Target is typical of a mass-market retailer, but that’s not good.” Thomas, the company’s spokesman, says: “Target is committed to responsible business conduct and this includes respect for workers’ rights.” The retailer publishes a list of the factories it uses for its brands and pledges not to work with vendors who hire child labor or require more than a 60-hour workweek. It says it regularly audits suppliers to make sure they’re complying with the company’s social responsibility requirements.

Cat & Jack wasn’t the favorite when the marketing team tested three names for the line last summer. Another name—which executives don’t want to share in case they find a use for it later—was the most popular, but that was because the group thought it sounded like “a basic brand with really great value,” says Michelle Mesenburg, vice president for style marketing. In other words, like the Target that Target doesn’t want to be. So they went with Cat & Jack, which sounds upscale, maybe a little vintage, while still, they hope, leaving a lot to the imagination. It may also sound a little familiar: There’s already a Janie and Jack brand, a Jack & Jill, and a Jack & Lily.

Like contemporary parents who give children so much decision-making power, Target is also learning about the institutional confusion that comes when children are really seen and heard. Kids will be involved in the Cat & Jack marketing campaign. Their photos will be in ads and in stores and when Target’s back-to-school promotion begins in late July. Some of those ads and social media spots will be written and directed by kids, too. The professionals are figuring out when and how much to be involved. At first, “we didn’t want it to be ‘made by kids,’ with us giving them all kinds of direction,” Jones, the chief marketing officer, says. Now he says he’s worried that “if these kids are really good, will it look like it’s made by kids?”—in other words, Cat & Jack can’t look too grown-up. A few weeks after that conversation, Target decided to also make its own, adult-directed Cat & Jack TV commercial to air in July.

Cat & Jack will be the second brand Guggemos and her team will have introduced this year. The first, Pillowfort, is for kids’ bedrooms and includes bunk beds, desks, sheets, and accessories. Target sold all those items before, but didn’t put a lot of design effort into them. Now there are lots of prints and patterns to be mixed and matched for boys and girls. Pillowfort is selling 15 percent better than the old stuff was, and Cornell says it could double the kids’ home business line over the next three years.

The attention, investment, and pressure on new brands such as Pillowfort, part of Cornell’s signature categories, are so far paying off. Sales for the brands and categories rose more than three times as fast as the company average in the first quarter of 2016. But overall, it was an underwhelming start to the year. Target’s same-store sales rose 1.2 percent for the period, less than expected. Cornell, like executives at many other retailers, blamed “an increasingly volatile consumer environment” and bad weather in the Northeast. He says that figure could be flat or down as much as 2 percent in the second quarter. It would be the first time sales have declined since he took over. Still, Cornell says, “the elevated focus we’ve applied to our signature categories is proving out, but we’re just at the beginning of the journey.”

Customers and the economy will decide whether Target bought the plane tickets to the most profitable final destination. “Those signature categories have been growing quickly,” says Kantar Retail’s Koo, “but there’s only so much of that stuff you can get people to buy. They still have to get the basics, like groceries, right.” Those are what bring people into the stores regularly. Cornell knows that families don’t need new clothes as often as they need food, but they need new clothes more frequently than industrial-chic filament-bulb string lights and stuffed giraffe heads for a child’s bedroom wall. Cat & Jack, then, is supposed to exist somewhere between the granola and the giraffe.

Back at Target headquarters in May, Steklenski says she’s started working on a “truly fashion aesthetic” line for kids that will arrive in stores in 2017. Everyone likes to feel they can control their destiny. Cat & Jack won’t be all that determines Target’s future, but the brand might help it, as the T-shirts say, “Dream Like a Unicorn.” Or at least “Run Hard,” and maybe “Win Big.”

No comments:

Post a Comment